We have already mentioned in previous Corporate Treasury Newsletters that the public demand to make sustainable changes regarding the economy and society is considerably increasing in view of the advancing climate change. A special role in this process is attributed to the banking sector in particular, as banks can help initiate progress towards a greener future through targeted lending. As a result, lending is increasingly being made contingent on ecological, social and corporate governance factors, so-called ESG criteria (Environmental, Social and Governance). There is a growing awareness among companies of the relevance of sustainability and the changes it entails. So regardless of aggravated conditions for raising funds, a refusal to embrace such a sustainable transformation can result in serious operational disadvantages. This is why many companies are now seizing the opportunity to implement "greener projects". Such projects are often financed with the help of equally "green" forms of financing, with funds that can only be invested in sustainable projects. These include green bonds, green loans and green promissory notes, which are being issued by an increasing number of companies.

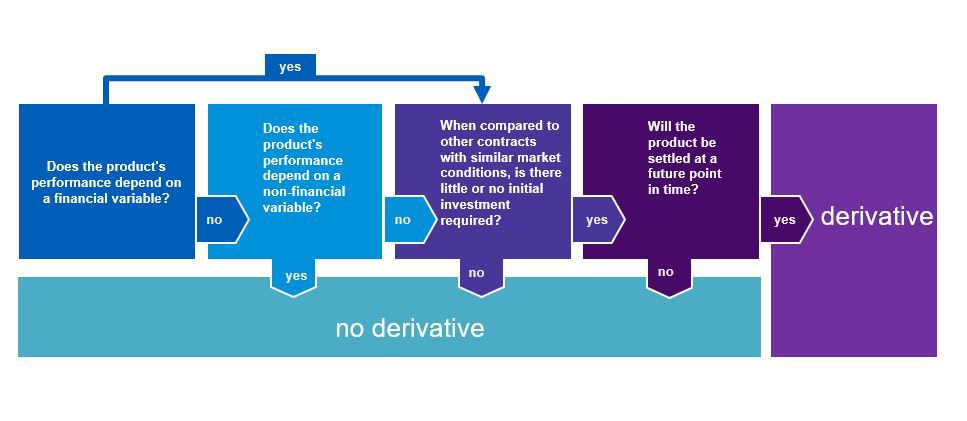

By way of example, our article deals with the accounting of a sustainability linked bond (SLB) in accordance with IFRS from the perspective of an issuer. SLBs constitute a distinct type of green financing instrument for which the sustainability criteria or objectives attached to the bond may change the financial and/or structural characteristics of the SLB. If, for example, an issuing company fails to meet an agreed sustainability target, this can significantly increase the interest burden and, as the case may be, have an impact on the balance sheet on the effective interest rate or the amortized cost. Depending on the contractual arrangement, it is possible that an embedded derivative is issued with the SLB. Under IFRS 9, the entity may then be required to account for the embedded derivative separately from the bond, subject to a separation requirement. When recognizing an SLB in the statement of financial position, it must therefore first be determined whether an embedded derivative exists at all and then whether it must be accounted for separately in accordance with IFRS 9. One fundamental prerequisite is that the SLB is a hybrid financial instrument that is not measured at fair value in subsequent periods. Should this be the case, the first step is to check whether an embedded derivative exists according to the following illustration.

Graphic: Defining characteristics of a derivative under IFRS 9.A

Source: KPMG AG, according to IFRS 9.A

Once an embedded derivative is identified, then the second step is to assess whether the embedded derivative must be accounted for separately or whether it is closely related to the host contract, in which case it would not be required to be accounted for separately. Admittedly, IFRS 9 does not provide a general definition of what constitutes a close link to the host contract. However, it does provide certain characteristics that indicate a close relationship. These include, for instance, having both the host contract and the embedded derivative subject to the same risk factors.

Taking the following examples, it should become clear which critical criteria or questions have to be examined in order to answer the question of whether an embedded derivative has to be accounted for separately. Essentially, it is about examining a financial vs. non-financial variable and whether the latter is specific to the issuing company (see test scheme above) as well as the embedded derivative's link to the host contract. For simplicity's sake, we will assume that both questions regarding the (low) initial investment and the product's settlement at a later point in the future have been met at this point.

Case 1:

Company A issues a 7-year SLB with a 3% coupon p.a. and wishes to use the financing from the issue to reduce its CO2 emissions. If by the end of year 3 Company A manages to reduce its emissions by 20%, the interest coupon is reduced by 50 basis points. If not, the coupon is increased by 50 basis points.

Company A's carbon emissions do not constitute a financial variable and are accordingly non-financial in nature. This raises the question of whether the non-financial variable can be specifically assigned to company A. Given that Company A's CO2 emissions can only be influenced by Company A and not by external influences, the emissions can be specifically attributed to Company A. As a consequence, there is no obligation to separate an embedded derivative in this case.

Case 2:

Company B issues a 5-year SLB. The coupon amounts to 2% p.a.. Simultaneously, it is agreed to adjust the interest rate to the performance of the Nature Stock Index. Should the index rise by 4% in one year, the interest rate is reduced by 20 basis points. Otherwise, the interest rate is increased by 20 basis points.

Unlike in case 1, the changes in value are based on an index, which can be considered a financial variable. This makes the present case an embedded derivative. As far as the separate accounting obligation is concerned, it is clear that the bond is fundamentally subject to an interest rate risk, while the change in the Nature Stock Index represents a share price risk. The characteristics of this derivative are therefore not closely related to the host contract. As such, the embedded derivative is required to be separated and must be accounted for as a freestanding derivative at fair value through profit or loss in accordance with IFRS 9.

Conclusion

As the two illustrative cases presented above clearly show, it is not always immediately apparent whether an embedded derivative, which may be required to be separated, has also been issued in addition to the issued financing instrument. Such a situation always requires an extensive contractual analysis and may - as several other examples have already shown in practice - depend on just one variable. So, if you intend to use a sustainability-linked bond or similar green financing instrument, for example, you should consider the full accounting implications before signing the contract. Our team at KPMG will be happy to assist you and offer independent advice on the design of your financing instruments.

Source: KPMG Corporate Treasury News, Edition 133, June 2023

Authors:

Ralph Schilling, CFA, Partner, Head of Finance and Treasury Management, Treasury Accounting & Commodity Trading, KPMG AG

Dr. Christoph Lippert, Senior Manager, Finance and Treasury Management, Treasury Accounting & Commodity Trading, KPMG AG

Ralph Schilling

Partner, Financial Services, Head of Finance and Treasury Management

KPMG AG Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft