Jump to: Context | The EU Unshell Directive proposal | KPMG survey | Beneficial ownership | Governance | Substance | Conclusion

Context

The fight against tax avoidance and profit base erosion has been high on the agenda of international bodies – including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission (the Commission), as well as local tax authorities for the last decade.

At the level of the OECD a significant development in recent years has been the introduction of anti-abuse measures into existing double tax treaties through the Multilateral Instrument (MLI). The aim of the Multilateral Instrument was to implement the tax treaty related recommendations from the OECD BEPS Action Plan, including a minimum standard to prevent treaty abuse[1].

At EU level, in parallel to Member States signing up to the OECD MLI, approaches to abuse of double tax treaties and EU Directives have also been influenced by the decisions of the Court of Justice of the EU in the so-called “Danish cases[2]”.

The "Danish cases" addressed two main issues: guidance on the interpretation of the beneficial owner concept in the context of the Interest and Royalties Directive (IRD) in particular[3], and the concept of abuse of rights under EU legislation. The cases involved cross-border intra-group payments of interest or dividends between companies that were tax residents in the EU and that benefited from withholding tax exemptions under the IRD and the Parent-Subsidiary Directive (PSD), respectively.

On the first point, in its decisions the CJEU confirmed that, for the purposes of the IRD, the beneficial owner is the entity that economically benefits and has the freedom to use and enjoy the interest. In this context, the CJEU emphasized the relevance of the OECD Model Tax Convention and the related Commentaries in interpreting the concept of beneficial owner under the IRD[4].

On the last point, the CJEU reaffirmed that EU law prohibits abusive practices as a general principle and concluded that under abusive circumstances, Member States are required to deny the benefit of an EU Directive, even in the absence of domestic or other anti-abuse provisions. The CJEU also provided guidance regarding the constitutive elements of an abuse of rights under EU law[5].

- Group structure: the structure was not set up for reasons that reflect economic reality, and its principal objective or one of its principal objectives was to gain a tax advantage that contradicts the intended goal or purpose of the relevant tax law

- Pass-through: all or nearly all dividend or interest income obtained by the intermediate company is passed on, shortly after being received, to another entity that would not have been eligible for withholding tax relief under an EU Directive

- Insignificant profits: the intermediate company's profits are insignificant since the dividend or interest income received is redistributed

- Absence of economic activity: this element needs to be analyzed in the light of the specific features of the economic activity in question, and by looking at all relevant factors including the management of the company, its balance sheet, the structure of its costs and expenditure actually incurred, employees, premises and equipment

- Right to use and enjoy dividends: contractual obligations (both legal and actual) which render the intermediate company unable to enjoy and use the dividends

- Timing: there is a close connection between the establishment of complex financial transactions and structures and new tax legislation.

As a side note, the CJEU has also clarified in case C-504/16 the mere fact that the economic activity of an entity consists in the management of assets for the group or that the income of that company results only from such management cannot, per se, indicate the existence of a wholly artificial arrangement which does not reflect economic reality. Instead, in the CJEU’s view,

CJEU stated that a tax authority has the task of establishing the existence of the elements constituting the abuse, based on specific facts and circumstances. The CJEU further noted, specifically, that if tax authorities deny a benefit under an EU Directive because the company receiving the income is not its beneficial owner, such authorities are not required to identify the beneficial owners of the income. It is sufficient to establish that the alleged beneficial owner functions as a conduit company through which an abuse of rights has occurred.

The CJEU’s comments on beneficial ownership in the context of the IRD and the guidance on the constitutive elements of an abuse of rights under EU law provide some clarity on these concepts. These clarifications complement the Court’s previous case law, which noted that the mere fact that the economic activity of an entity consists in the management of assets for the group or that the income of that company results only from such management cannot, per se, indicate the existence of a wholly artificial arrangement which does not reflect economic reality[6]. However, as the CJEU was only in a position to provide suggestions on the possible indications of abuse (it is up to national courts to decide on the specific circumstances of the case referred), the legacy of the Danish cases is nevertheless an increased scrutiny of intra-group dividend and interest payments, in particular where intermediate companies are present in the group’s EU structure, without clarity on the interpretation of the abovementioned concepts. The resulting unharmonized and inconsistent approach to the evaluation of potential abuse in the context of intra-group payments means that the evaluation of a taxpayer’s access to reduced withholding tax (WHT) rates (under domestic, EU or treaty law) has become increasingly volatile therefore leading to significant uncertainty and an increased volume of disputes between tax authorities and taxpayers.

The EU Unshell Directive proposal

Against this backdrop, the European Commission is attempting to take steps towards establishing a common minimum standard on criteria for denying treaty or EU Directive benefits to companies lacking economic substance and which are at risk of being misused for the purpose gaining tax advantages through a proposal for an EU Directive commonly known as "Unshell”[7]. The Unshell proposal sets out a list of features, referred to as gateways, to filter entities at risk of being misused for tax purposes. High-risk entities would then be required to report on a series of substance indicators through their annual tax return. Companies failing to meet a set of substance indicators would be deemed to be ‘shell’ entities, potentially triggering the denial of certain tax benefits that would have otherwise been available under double tax treaties and EU Directives.

Nearly two years since its introduction, the proposal is still under negotiation among EU Member States, with its final text and date of application remaining unclear. It could be inferred from the length of time during which discussions were held among Member States that the final text will differ from the initial proposal. Nonetheless, it's important to note that the original European Commission proposal is the only official position currently publicly available and has been used as a reference for the purposes of this article.

The totality of the anti-abuse framework, the broader concept of abuse of law, domestic substance requirements and anti-conduit rules, and the availability of certain WHT benefits only to the beneficial owner of the income are all pieces of the complex puzzle that needs to be solved by taxpayers claiming withholding tax relief. The present text intends to provide an overview of the disparities in approaches across Member States within these areas. Understanding these differences is key for taxpayers when assessing the withholding tax treatment for cross-border intra-group flows of dividends, interest, or royalties.

KPMG survey

With these developments in mind, in 2022 KPMG’s EU Tax Centre (the ETC) conducted an internal survey across the network of KPMG firms based in Europe to understand beneficial ownership (BO) trends across the EU and to collect key insights regarding the practice of local tax authorities in this area. We presented the outcome of our first survey in a previous blog post last year[8].

The ETC has continued to monitor developments in this area, most recently with a further internal survey, which was conducted in the Summer of 2023. Specifically, KPMG firms across Europe were asked to respond to an updated survey with an extended scope of queries. The objective of the survey was to identify common trends and key challenges for taxpayers in four main areas:

- beneficial ownership;

- substance;

- corporate governance;

- the wider anti-treaty shopping and anti-tax abuse frameworks applicable at a local level, with a particular focus on WHT-related measures; and

- the practice of the tax authorities in BO and substance matters, and level of certainty taxpayers can obtain.

The questions were asked in the context of intra-group transactions between associated companies, and do not necessarily reflect the tax treatment of income flows related to portfolio holdings.

The revised survey includes responses from 27 European jurisdictions[9] and includes survey information valid as at September 2023. This article outlines key findings and trends identified as a result of the survey. Note that all information is valid as at September 2023. The information included below is of a general nature and does not represent tax advice based on entity-specific facts and circumstances. No one should act on such information without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation.

Beneficial ownership

Key insight: The beneficial ownership concept continues to be applicable in the majority of EU countries.

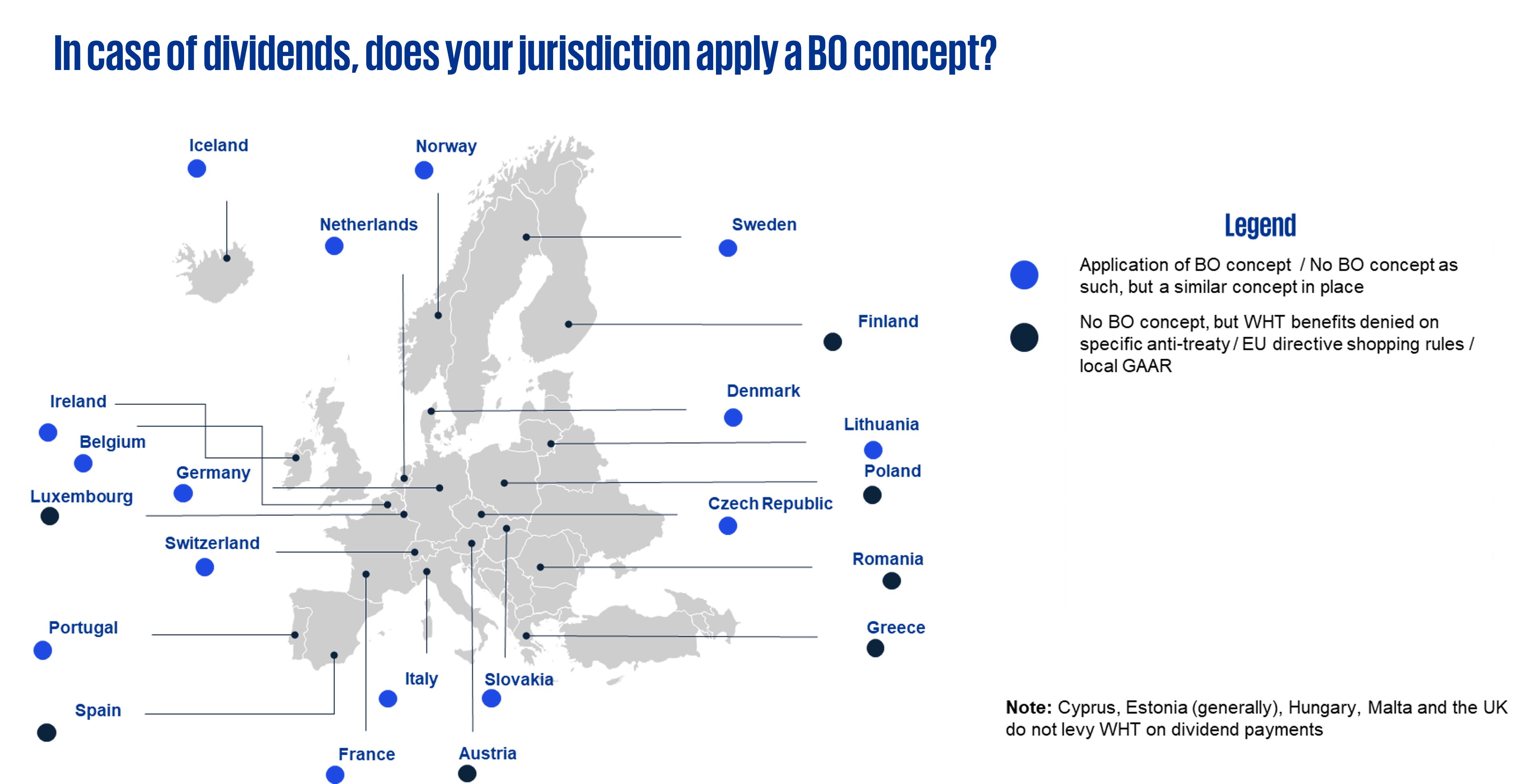

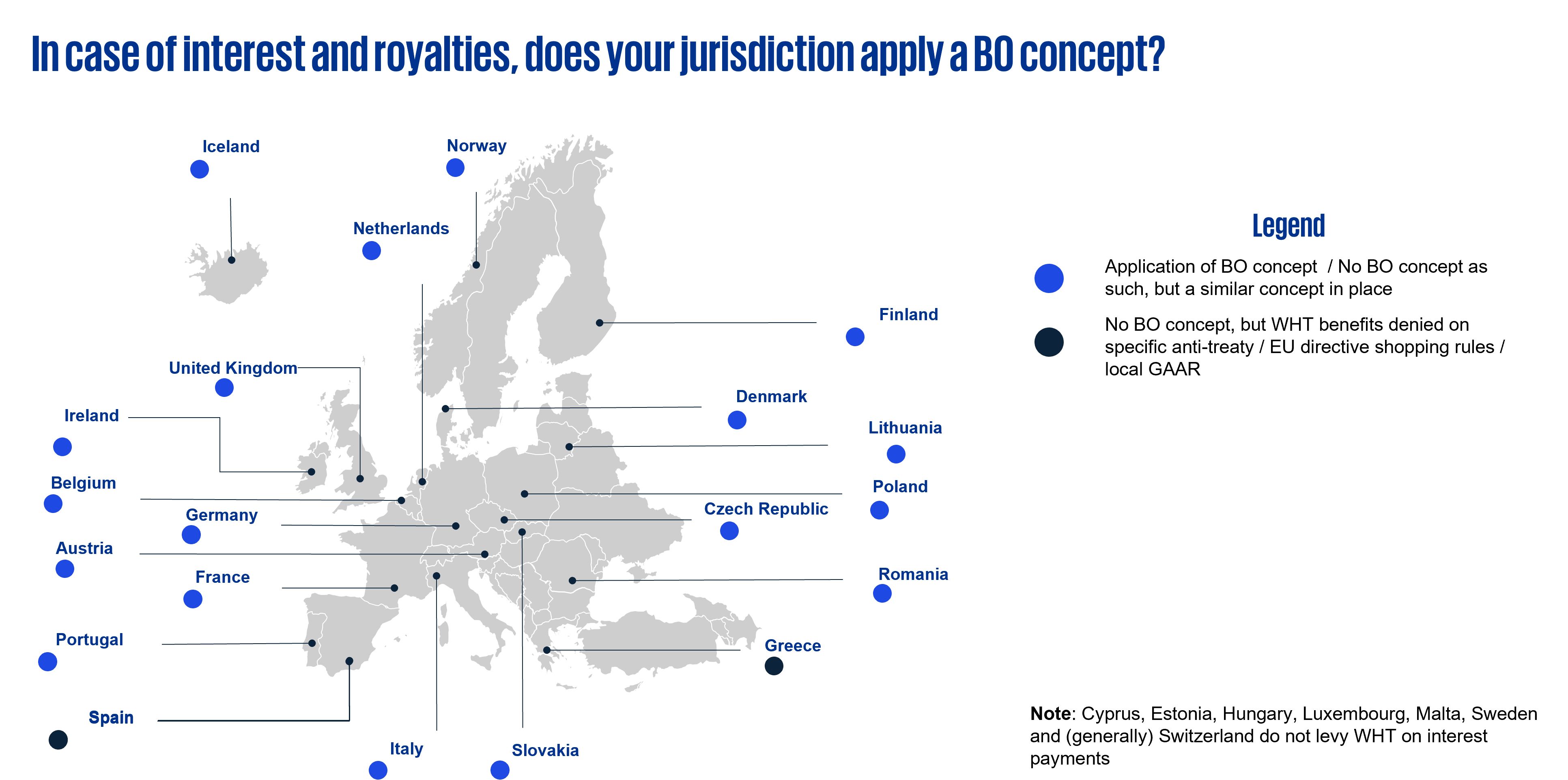

The survey revealed that in a substantial number of responding jurisdictions, beneficial ownership, or similar concepts, hold significant relevance when it comes to the correct application of WHT rates. Specifically, this concept is applicable in 54 percent of jurisdictions applying WHT on dividend payments, and an even more significant 71 percent when it comes to interest and royalty payments. The difference is explained by the fact that certain jurisdictions (e.g. Greece, Poland and Romania), rely on a legal ownership test rather than a BO test when testing ownership of shares and resulting income.

The graphics below illustrate the importance of the beneficial owner concept across the responding jurisdiction.

In certain instances, it is not entirely clear whether a beneficial ownership requirement exists. For instance, the Icelandic Tax Code does not refer to beneficial ownership as such; however, in order to apply for WHT benefits under a double tax treaty, an applicant must confirm their status as the beneficial owner on the application form. Similarly, in Ireland, when transposing the Parent-Subsidiary Directive, in line with the PSD an explicit reference to BO was not included. Nevertheless, the references to ownership in the relevant provision are generally understood to imply a beneficial ownership requirement. On the other hand, the local Irish dividend WHT exemption for outbound payments of dividends to treaty countries applies only to cases where, among others, the recipient is "beneficially entitled" to the dividend.

Interestingly, while the Parent-Subsidiary Directive does not test whether the recipient of the dividend is the beneficial owner of the income when providing relief from withholding tax , jurisdictions such as the Czech Republic have included this test in their domestic law when implementing the Directive.

Germany has also adopted a strict position whereby the local Tax Code incorporates an anti-treaty/directive shopping provision that denies the reduction of WHT if (i) the recipient is not the beneficial owner of the income and, (ii) if its shareholders (assuming they are the beneficial owners) would not be eligible for the treaty/directive benefits had they made the investment directly (additional conditions also apply).

Other jurisdictions, such as Norway and Sweden do not make any reference to the concept of BO in their domestic law, however, similar concepts apply. Norwegian jurisprudence suggests that there may be similarities in determining whether the direct recipient is entitled to treaty benefits, whereas, Swedish law restricts the applicability of WHT benefits to the party that holds “the right to the dividend income” (i.e. defined as the person who is entitled to withdraw a dividend for their own account at the time of the dividend payment).

In spite of a lack of harmonization of the beneficial ownership concept under the OECD Model Tax Convention or at the level of the European Union law, a small number of individual Member States have recognized the lack of clarity around this concept and have taken steps to address this issue for investors seeking to access reduced WHT rates in their jurisdictions.

A first example comes from Slovakia, where a BO definition has been included in the local Tax Code since January 2018. However, the definition did not initially provide guidance on how taxpayers could substantiate their BO status. This was resolved in August 2023, when the Financial Directorate of the Slovak Republic issued supplementary information on the method of substantiating the status of beneficial owner of the income. While this provided valuable guidance, it's worth noting that the information offered is framed as a recommendation and, therefore, not legally binding. Nevertheless, it represents a significant step towards establishing a framework for demonstrating BO status and hence for the application of double tax treaties.

Poland is another jurisdiction that has taken recent steps to provide more clarity. On September 28, 2023, the Polish Ministry of Finance issued draft clarifications on the interpretation of the beneficial owner concept, as well as establishing a framework for the due diligence requirements to be caried out by the income payor.

In other jurisdictions, while an explicit definition is not available in their local Tax Codes, indicia can be drawn from local administrative guidance or jurisprudence. For example, in Belgium, local case-law and administrative commentaries provide a basis for the indicators that are taken into account when determining beneficial ownership[10]. A similar situation exists in Iceland, where – regardless of the absence of a reference to beneficial ownership in the local Tax Code, in practice, BO is essential when seeking treaty WHT rates, and the application form for reduced rates includes an interpretation of the concept according to the Icelandic Director of Internal Revenue[11].

Italy only defines beneficial ownership in the context of interest and royalty payments in its local Tax Code. Nonetheless, when it comes to dividend payments, the relevance of establishing the beneficial owner can be inferred from legal precedents and administrative practices, which also refer to the OECD principles and interpretations.

In the UK, although it is necessary to determine if the recipient of a payment is the "beneficial owner" for purposes of applying a double tax treaty WHT rate for interest and royalties payments, no explicit definition of this concept exists in UK domestic tax law. The interpretation of the term remains uncertain in the context of the UK's tax treaties as the responses did not reveal case-law specifically dealing with the meaning of beneficial ownership in this context. In principle, the OECD commentary should apply to the extent relevant to the interpretation of the treaty in question. However, in practice, HMRC have looked to economic tests (e.g. relying on the decision in case A3/2005/2497

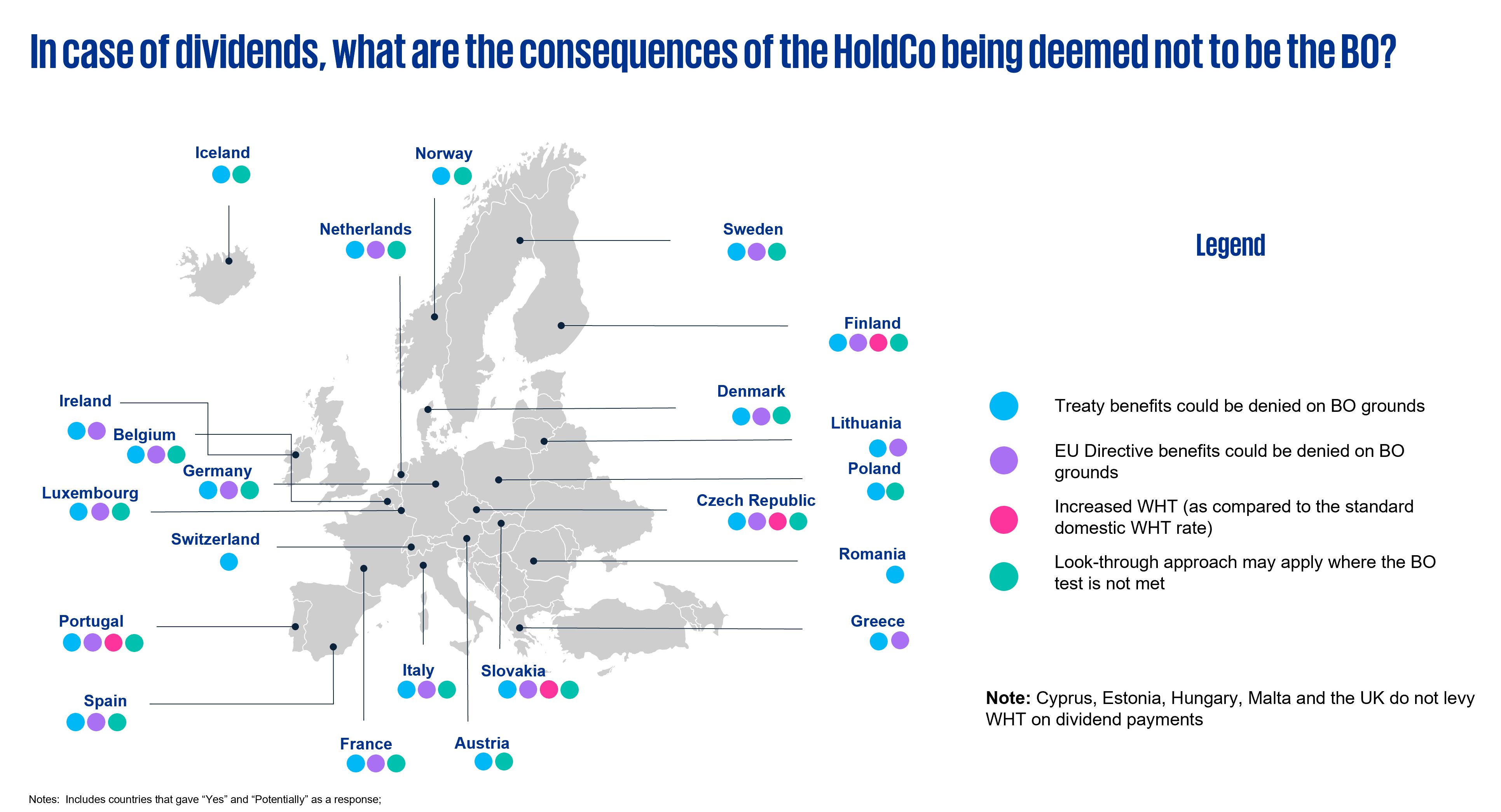

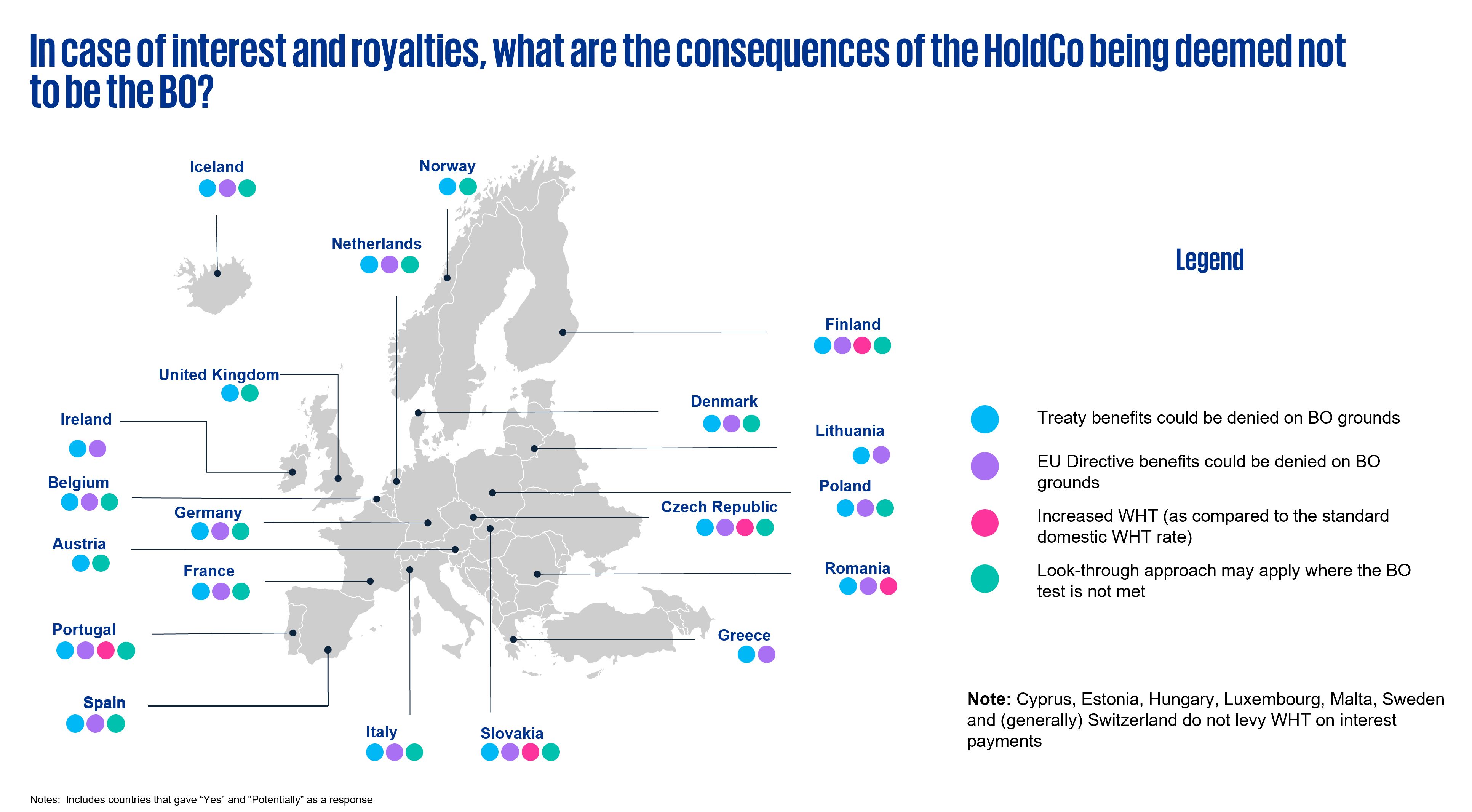

Key insight: Failure to meet the beneficial ownership criteria can lead to the denial of EU Directive or double tax treaty benefits, with some countries imposing higher WHT rates.

Generally, in jurisdictions applying a BO concept, failing to meet this requirement would result in the denial of EU Directives or double tax treaty benefits. Denying the BO status can lead to additional tax consequences in several jurisdictions.

In the Czech Republic, Finland, Portugal, Romania (interest and royalties only) and Slovakia, an increased punitive WHT rate might apply. In the Czech Republic, if the immediate recipient is not considered the beneficial owner of the dividend, a 35 percent aggravated WHT may apply, rather than the domestic or treaty rate. The increased rate generally applies in cases when the direct recipient is not a resident of the EU or a treaty country (double tax treaty or exchange of information). However, it is likely that it would also apply if the taxpayer is unable to substantiate the tax residence of the beneficial owner in the EU or a treaty country. A similar increased 35 percent WHT rate could apply in Portugal, in specific situations. Slovakia also imposes an increased 35 percent WHT rate if the beneficial owner cannot be identified or is tax resident in a non-cooperative jurisdiction.

In Romania, a punitive WHT rate of 50 percent is applicable for royalty and interest payments if two conditions are met simultaneously: (i) the transaction is classified as artificial, according to the general anti-abuse rule specified in tax law, and (ii) the income is paid to a bank account from a state that has not established any information exchange treaty with Romania.

Denmark also applies an increased WHT for dividend payments if the beneficial owner is resident in a jurisdiction included on the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes.

Key insight: Inconsistent look-through approach.

The survey also revealed a further inconsistency in the EU regarding the application of the look-through approach. Specifically, in 19 percent of the jurisdictions, higher-tier group companies that qualify as the (ultimate) beneficial owners of dividend payments, would typically not be able to claim WHT benefits in the source state, even where they would have benefited from the same rate in the case of a direct investment. The percentage is slightly lower for interest and royalty payments (i.e. 17 percent of the jurisdictions would not allow a look-through approach). Further to this point, in several jurisdictions where the look-through approach is possible, the practices of the local tax authorities in applying the approach is not consistent.

As mentioned in our introductory comments, the CJEU held in the Danish cases that tax authorities that challenge beneficial ownership at the level of the recipient are not required to identify the actual beneficial owners of the income. In line with these judgments, taxpayers should not assume that a look-through approach will be automatically applied. Instead, they may attempt to present evidence to tax authorities to establish the identity of the beneficial owner and request the application of EU Directives or treaty benefits for this beneficial owner, where available. Several countries have indicated that, in this case, if presented with sufficient evidence, the tax authorities might consider a look-through approach. This is the case for example in Belgium, where this approach also represents a departure from the past practices of the local tax authority. In the case of France, case-law shows that the local courts have started to recognize the applicability of the tax treaties between the source state and the state where the beneficial owner of the payment (other than the direct recipient) is tax resident.

It is important to note that the look-through approach may not be available in the case of benefits granted under an EU Directive, even where such an approach is typically applied for double tax treaty benefits. This could be the case, for example, in Italy and Spain. In both cases, a look-through approach may be achieved based on a case-by-case assessment by local tax authorities or as a result of court proceedings. Consequently, WHT treaty relief could be extended up the ownership chain to the entity proven to be the beneficial owner. However, exemptions are generally not granted based on the Parent-Subsidiary Directive or the Interest and Royalties Directive. This is due to the absence of references to indirect shareholding in the local implementation of these Directives[12].

Similarly, a look-through approach could apply in the Netherlands, but only concerning the applicability of double tax treaties and not for the domestic WHT exemptions. The same approach is followed in Poland, where no look-through approach is available in the context of the Parent-Subsidiary Directive (but WHT relief could be granted based on the relevant double tax treaties).

The UK took a further step in reducing uncertainty and adopted guidance[13] illustrating how the look-through approach would apply for interest flows, on which the UK levies withholding tax. As such, the guidance notes that treaty relief will not be denied merely because the immediate recipient is not the true beneficial owner of the payment. This remains valid as long as the actual beneficial owner would have been eligible for the gross payment (meaning no UK WHT would be applicable) under the relevant treaty.

In the aftermath of the Danish cases, the look-through approach is generally applied in Denmark where the direct recipient of the dividend, interest or royalty payments is deemed not to be the beneficial owner. In such instances, the payments would be subject to taxation as if they were made directly to the beneficial owner. The related WHT could be reduced based on the applicable EU Directives or the double tax treaty in force between Denmark and the jurisdiction where the beneficial owner is tax resident. This approach was confirmed by the Danish Supreme Court ruling[14] on January 9, 2023, in two cases[15] from the ”Danish cases” series on the WHT exemption under the EU Parent-Subsidiary Directive. The Danish Supreme Court concluded that the taxpayer proved that its US parent was the beneficial owner of the second dividend distribution and as a result, the benefits of the Denmark-US double tax treaty should be applied.

It is important to note that, based on the practice of the Danish courts, the burden of proof lies with the taxpayer to establish the identity of the beneficial owner of the payment. As such, in its May 4, 2023 ruling[16] regarding two cases concerning WHT exemption under the Interest and Royalties Directive, the Danish Supreme Court concluded that it could not ascertain the beneficial owner due to the limited evidence presented by the taxpayers. Consequently, the payments were subject to domestic Danish WHT, and no double tax treaty benefits were granted.

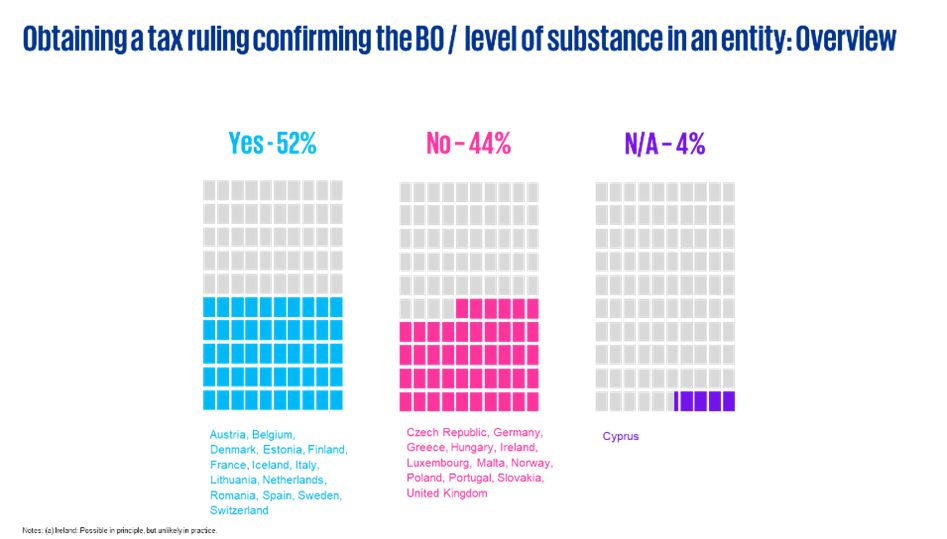

Key insight: Mixed outcomes in pursuit of advance tax rulings on beneficial ownership.

On the topic of advanced certainty, survey results highlight that only half of the responding jurisdictions noted that taxpayers could obtain advance tax rulings in their jurisdictions to confirm the BO status of a taxpayer. This implies a significant degree of uncertainty for businesses operating globally and it also underscores the importance of a comprehensive understanding of each jurisdiction’s specific tax laws and regulations and the need for taxpayers to maintain appropriate records to meet the burden of proof placed upon them.

Governance

The survey also covered corporate governance requirements in the surveyed jurisdictions. The aim was to identify instances where an entity that is not incorporated in a jurisdiction may nevertheless be deemed to be tax resident therein based on criteria such as effective management or control (e.g. under what circumstances – if any, would the German tax authorities deem tax resident in Germany an Irish incorporated entity).

Key insight: Place of effective management is the predominate concept in the majority of surveyed jurisdictions.

Interestingly, two of the Baltic countries (Estonia and Lithuania), as well as Sweden, indicated that neither the POEM, nor the CMC concepts is relevant in determining residence. It has been reported that the Estonian tax framework does not currently provide a legal basis to determine that a company incorporated in another jurisdiction could be tax resident in Estonia. In Lithuania and Sweden, the sole indicator used to determine tax residency is the place of incorporation. However, irrespective of the above, readers should note that the mere fact that a company is not considered tax resident in these jurisdictions does not automatically imply that no tax consequences could be triggered. For instance, the activities conducted in these jurisdictions could potentially give rise to local permanent establishments, which would then be subject to taxation[17].

In those countries that do apply rules that can deem a foreign incorporated entity to be tax resident in their jurisdiction, it was noted in the survey that local tax authorities rely on various criteria, such as the Place of Effective Management (POEM)[18] or whether Central Management and Control (CMC)[19] functions are carried out in the jurisdiction. The survey revealed that 70 percent of the surveyed jurisdictions assess tax residency by applying the POEM concept, whereas approximately 15 percent of jurisdictions apply the CMC concept.

Poland provides yet another interesting example, where the domestic Tax Code does not use the POEM rule as such but does provide an illustrative example of a situation in which the place of management is deemed to be located in Poland. There are similarities between the illustrative example provided in the Polish code and characteristics of the POEM concept, but the two are not identical.

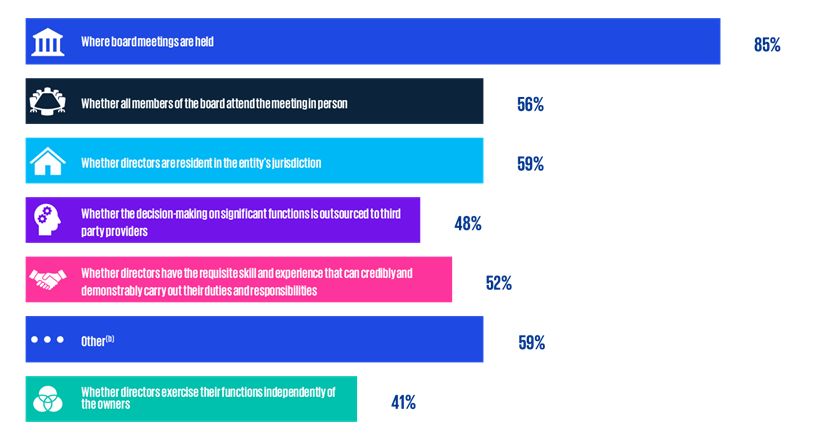

Key insight: Location of board meetings relevant when determining tax residence in the vast majority of surveyed jurisdictions.

The starting point in most tax residency assessments is that the analysis should be performed on a case-by-case basis, considering all the facts and circumstances of a particular entity. Consequently, where guidance is provided by tax authorities regarding the list of factors deemed relevant when assessing tax residence, it is typically only indicative and non-exhaustive in nature. Nevertheless, the responses received revealed some common trends in the factors that could be examined or considered, when determining tax residence based on the POEM, CMC or other domestic principles.

The location of board meetings was considered a relevant factor in 23 out of 24 relevant surveyed jurisdictions[20]. It is important however to bear in mind that the mere location of board meetings would not necessarily be determinative. For example, guidance issued by the UK tax authority (HMRC)[21] clarifies that there is no assumption that the CMC of an entity must be found to be where board meetings are held. In such a case, it would be critical to verify that CMC is not actually exercised outside board meetings, for example, by (i) a parent or shareholder of the company in question, (ii) the CEO or executive management team, or (iii) an adviser or other third party to whom functions are outsourced.

Other relevant criteria in the majority of jurisdictions include (i) the physical presence of all board members at meetings held in that jurisdiction (63 percent of relevant surveyed jurisdictions) and (ii) the facts and circumstances of the company's directors. Other criteria that are widely used include the residence of directors (in 67 percent of relevant surveyed jurisdictions), and the skills and experience of directors (in 58 percent of the jurisdictions).

As a final point on this matter, it should be noted that the weight given to each criterion, such as the ones listed above, can vary depending on the jurisdiction. As such, understanding the relevance of each indicator remains essential for businesses operating internationally and typically requires a case by case analysis.

Key insight: Several gateways and substance indicators proposed under Unshell align with the factors typically considered when determining tax residence of companies.

Another interesting aspect revealed by the responses is that several criteria proposed under the Unshell initiative are applied in determining tax residency in the majority of surveyed jurisdictions. For example, adequate nexus – such as directors being physically present in that jurisdiction and possessing the necessary expertise to fulfill their duties, which is one of the substance indicators included in the European Commission’s initial proposal is used as a criterion when assessing residence by several European jurisdictions.

A similar parallel could be drawn in respect of outsourcing decision-making to third party providers. As such, in almost half of the countries included in the survey, retaining decision-making authority over significant functions within the organization (as opposed to outsourcing them to third party service providers) is a relevant factor in determining tax residency. Under Unshell, for the purpose of testing substance, the EC’s proposal required that at least one of the company’s directors to be neither employed by a third party nor engaged in a similar capacity for other third parties.

Substance

Survey responses also revealed the diversity of factors that tax authorities typically consider when evaluating economic substance, including (non-exhaustive):

- the company's management (i.e. whether the locus of decision-making authority is within the jurisdiction where the company is registered)

- balance sheets

- the structure of costs and expenditures (i.e. expenditures are expected to be proportionate to the operational scope of the entity

- other factors such as the size of the workforce, and the ownership of premises and equipment. WHT specific anti-abuse measures

Key insight: Additional specific WHT anti-abuse provisions are in place in multiple jurisdictions.

The mere absence of the BO concept in certain jurisdictions does not automatically imply that WHT reductions are available without further scrutiny. For instance, when it comes to dividend payments, Austria could contest the eligibility for reduced rates based on its local economic ownership concept. Additionally, formal substance requirements are applicable for Austrian WHT relief under the Parent-Subsidiary Directive. As such, shareholders are required to provide a written statement indicating that they (i) derive income from active business, (ii) have their own personnel, and (iii) maintain their own business facilities.

Another example is Spanish tax law, which does not include a beneficial owner clause in the case of dividends but does include an anti-abuse clause that denies the EU Parent-Subsidiary exemption when more than 50 percent of the shares in the EU entity are ultimately owned by non-EU investors. In such instances, the taxpayer must demonstrate that the decision to hold the entity through an EU parent is not primarily tax-motivated, and that there are valid business justifications and economic reasons for the chosen structure. In practice, this often requires the presence of substantial business activities by the EU entity.

Similarly, in the case of the Spanish domestic WHT exemption for interest received by EU residents, there are no specific anti-avoidance rules or beneficial owner requirements outlined in the law. Nevertheless, in practice, tax authorities have historically challenged the interest WHT exemption in cases involving back-to-back loan structures with non-EU lenders (in cases not rebutted based on commercial and business reasons).

Conclusion

The most obvious conclusion from the results of this internal survey is the variety of approaches among European jurisdictions in terms of the relevance of the beneficial ownership concept (and its use as an anti-abuse measures) and the factors that are considered significant when assessing governance (where relevant) and economic substance. Increased interest in the scrutiny of cross border payments of passive income, whether based on grounds related to beneficial ownership or governance and economic substance criteria has been observed in a significant number of jurisdictions. Whilst it was not the intention of this exercise to identify the triggers, it is probably reasonable to assume that this observed trend is the result of a multitude of factors such as the OECD’s BEPS project, the introduction of anti-abuse measures in the EU and relevant CJEU case-law.

With regard to the CJEU’s conclusions in the Danish cases, beyond Denmark, several other countries have documented instances where local tax authorities directly invoked the criteria established in the European Court’s decision when assessing the applicability of reduced WHT rates. Whilst some common trends can be observed and domestic and EU jurisprudence, as well as the European Commission’s proposed Unshell directive, may provide some guidance on the concept of beneficial ownership on one hand and on the existence of economic substance, on the other, the landscape remains heterogenous. Taxpayers are therefore encouraged to take into consideration the specifics of each jurisdiction when assessing their exposure to taxes on dividend, income and royalty income.

[1] Signatories were offered three options to meet this specific minimum standard, by implementing: (i) a principal purpose test (PPT) alone (default option), (ii) a PPT and a simplified or detailed limitation on benefits provision (LOB), or (iii) a detailed LOB provision, supplemented by a mechanism that would deal with conduit arrangements not already dealt with in tax treaties. The PPT would deny a treaty benefit in respect of an item of income or capital, if it was reasonable to conclude, having regard to all relevant facts and circumstances, that obtaining that benefit was one of the principal purposes of an arrangement or transaction that resulted directly or indirectly in that benefit, unless it was established that granting that benefit in the given circumstances would be in accordance with the object and purpose of the relevant provisions of the covered double tax treaties. All EU Member States have signed the MLI.

[2] Joined cases N Luxembourg 1 (C-115/16), X Denmark (C-118/16) and C Danmark 1 (C-119/16) and Z Denmark case (C-299/16) on the Interest and Royalties Directive and joined cases T Danmark (C-116/16) and Y Denmark (C-117/16) on the Parent-Subsidiary Directive. See Euro Tax Flash Issue 396 for more details.

[3] The IRD limits the withholding tax exemption to the beneficial owners of the interest. In contrast, the text of the Parent-Subsidiary Directive does not explicitly incorporate a beneficial ownership test concerning dividend payments.

[4] This alignment is rooted in the fact that the original IRD proposal was built on the OECD’s work in this matter.

[5] Under settled CJEU case-law, proof of an abusive practice requires, first, a combination of objective circumstances in which, despite formal observance of the conditions laid down by the EU rules, the purpose of those rules has not been achieved and, second, a subjective element consisting in the intention to obtain an advantage from the EU rules by artificially creating the conditions laid down for obtaining it. The presence of a certain number of indications may demonstrate that there is an abuse of rights, in so far as those indications are objective and consistent. While the Court cannot assess the facts in a specific case brought before it, the CJEU may nevertheless specify indicia that could lead to the conclusion that there is an abuse of rights. To this end, in the Danish cases, the CJEU provided illustrative examples that could indicate the existence of abuse in conduit situations.

[6] C-504/16. The CJEU also noted in that context that the existence of abuse requires, on a case-by-case basis, an overall assessment of the relevant situation be conducted, based on factors including the organisational, economic or other substantial features of the group of companies to which the parent company in question belongs and the structures and strategies of that group.

[8] Beneficial ownership trends across the EU - Beneficial ownership trends across the EU - KPMG Global

[9] Jurisdictions surveyed include the following: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK.

[10] Such indicators may include: having an active business, local board of directors meetings (with a preference for a majority of Belgian resident directors), employing one or more full-time personnel with authority to legally bind the company for day-to-day management purposes, having an office space (which may be leased), maintaining local bookkeeping, various assets on the balance sheet, and a local bank account.

[11] In this case, the beneficial owner is defined as an entity that enjoys the benefits of owning a security or property, irrespective of the name on the title.

[12] Consider the case of a parent entity that has a qualifying direct shareholding in an intermediate holding company and a lower tier-subsidiary. If a lower-tier subsidiary performs a dividend payment to the intermediate holding, and the latter does not satisfy the BO criteria, the parent company would be unable to claim Directive benefits. This limitation persists despite the parent's qualifying ownership in the lower-tier subsidiary because this ownership is not directly connected to the payment at hand (which is made to the subsidiary rather than to the ultimate parent).

[13] https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/international-manual/intm332060

[14] In the context of the Danish cases, the CJEU provided guidance on what could constitute abuse under EU Law. However, it was for the local Danish courts to assess whether the arrangements under review constituted an abuse based on the guidance provided.

[15] This ruling relates to cases T Denmark (C-116/16) and Y Denmark (C-117/16), the two joined Danish cases on the concept of BO of dividend distributions that were ruled on by the CJEU. Both cases concern dividend distributions made by a Danish resident company to an intermediate holding company resident in the EU. For more details, please refer to E-news Issue 169.

[16] The ruling relates to cases N Luxembourg 1 (C-115/16) and X Denmark (C-118/16), two of the four joined Danish cases on the concept of BO in respect of cross-border interest payments. For more details, please refer to E-news Issue 177.

[17] For further insights regarding potential permanent establishment risks in the EU, please see our recent blog post regarding same.

[18] POEM: the OECD Commentary suggests that the place of effective management of a company is ordinarily where the most senior person or group of persons (e.g. Board of Directors) makes its decisions, which normally corresponds to where it meets.

[19] CMC: the exercise of central management and control goes beyond the management on a day-to-day basis of the company’s normal business transactions. It concerns the exercise of strategic decision making by the highest decision-making authority for the company, which is usually the Board of Directors. Various factors can be relevant when determining the location of central management and control (e.g. where directors’ meeting are held, where major contracts are negotiated and concluded, where the company directors reside, where the company seal, minute books and share register of the company are kept).

[20] For the purpose of this section, relevant surveyed jurisdictions refer only to the 24 jurisdictions (out of the 27 surveyed jurisdictions) in which companies could be deemed to be tax resident even in cases where they are incorporated in a foreign jurisdiction.

[21] https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/international-manual/intm120130

Connect with us

Connect with us

- Find office locations kpmg.findOfficeLocations

- kpmg.emailUs

- Social media @ KPMG kpmg.socialMedia

Stay up to date with what matters to you

Gain access to personalized content based on your interests by signing up today